Rising Cases of Legionnaires' Disease in New York City

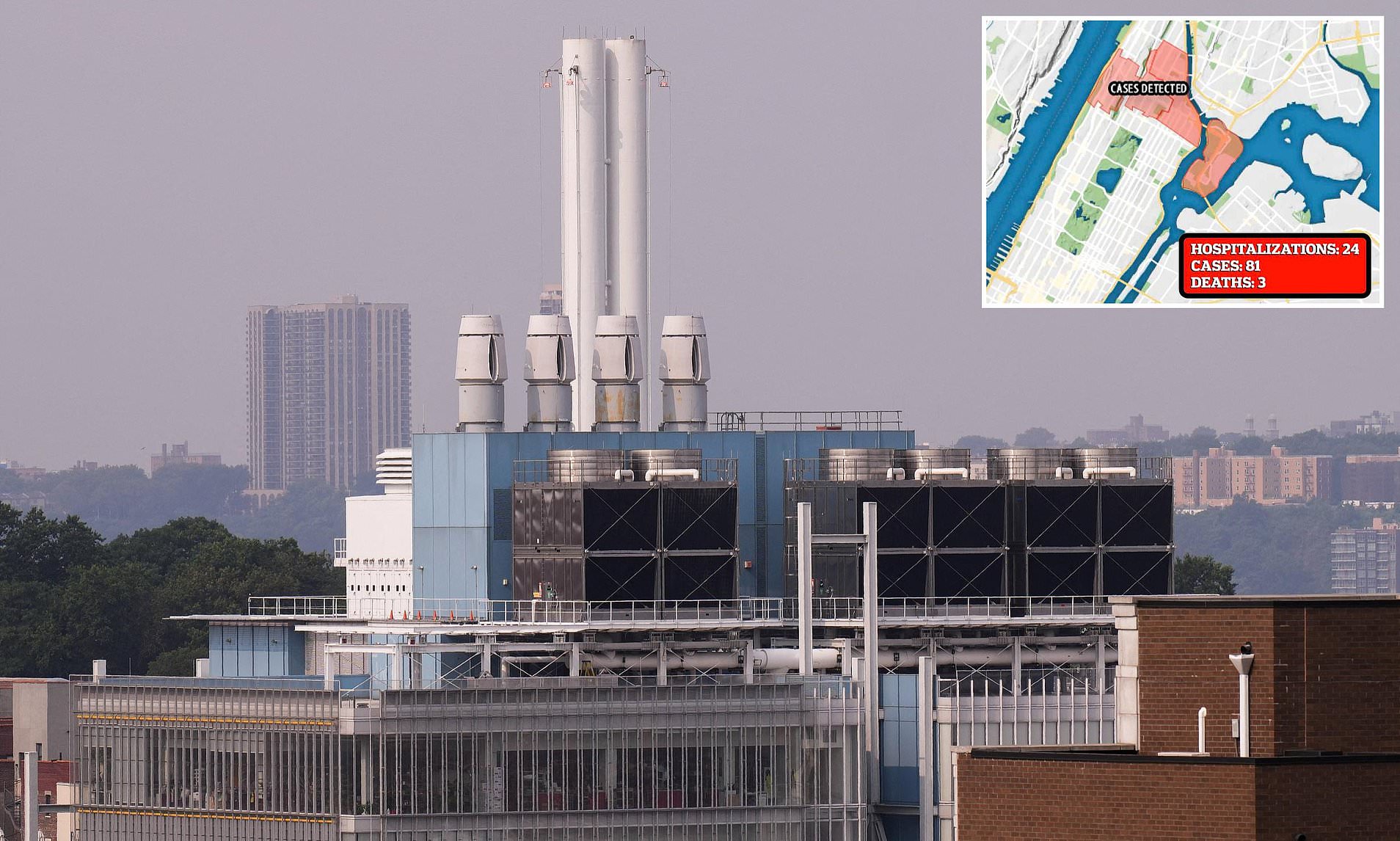

More New Yorkers are being infected and hospitalized with a deadly lung disease that is spreading across the city, according to health officials. As of August 7, approximately 81 individuals from upper Manhattan have been diagnosed with Legionnaires’ disease, a severe form of pneumonia caused by the Legionella bacteria. This bacterium thrives in warm water and can become airborne when water turns into steam, making it a serious public health concern.

The condition has led to the hospitalization of 24 people, with the most severe cases affecting older adults, smokers, and those with chronic lung diseases. All reported cases have been identified within five ZIP codes covering neighborhoods such as Harlem, East Harlem, and Morningside Heights. Although the exact source of infection has not yet been confirmed, officials believe that a cooling tower in the area is the likely culprit.

In a statement released on Thursday, the New York City Department of Health clarified that the issue does not stem from any building's plumbing system. Residents in the affected areas are advised to continue using tap water for drinking, bathing, showering, cooking, and operating air conditioners without concern. However, building owners are required to register their cooling towers and conduct routine water tests for bacteria. Reports indicate that inspections dropped to near-record lows before the outbreak, which officials attributed to staffing shortages.

Health officials emphasized that Legionnaires’ disease spreads through inhalation of mist containing Legionella bacteria. Potential sources include cooling towers, showers, and hot tubs. It is important to note that window air conditioners do not contribute to the spread of the bacteria. No official information has been released regarding deaths or specific details about hospitalized patients.

Infected individuals typically experience symptoms such as headaches, muscle aches, and high fevers, often reaching 104°F (40°C). Within three days, they may develop a cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and confusion. In severe cases, the disease can lead to life-threatening complications like pneumonia, sepsis, and organ failure.

Legionnaires’ disease affects an estimated 8,000 to 10,000 Americans annually, resulting in approximately 1,000 deaths. The five ZIP codes impacted in this outbreak are 10027, 10030, 10035, 10037, and 10039. While most people exposed to the bacteria do not get sick, those aged 50 or older, smokers, individuals with chronic lung conditions, or weakened immune systems are at higher risk.

Health officials urge anyone experiencing symptoms to seek medical attention immediately. Treatment typically involves antibiotics, which are most effective if administered early. Patients are often hospitalized, and recovery depends on prompt intervention.

Dr. Asim Cheema, a specialist in internal medicine and cardiology, highlighted that August is peak season for Legionnaires’ disease due to hot weather creating ideal conditions for bacterial growth. He warned that while the disease is treatable, it can be fatal if left untreated. In milder cases, individuals may suffer from Pontiac fever, a less severe condition that causes fever, chills, and muscle aches but resolves on its own without treatment.

The current outbreak was first reported on July 22, when the health department confirmed eight cases. Buildings found to have contaminated systems were ordered to clean them within 24 hours. This follows a similar outbreak in the Bronx in July 2015, which was the second-largest Legionnaires’ disease outbreak in U.S. history, infecting 155 people and causing 17 deaths. That outbreak was traced back to a cooling tower at the Opera House Hotel in the South Bronx.

To reduce the risk of infection, Dr. Cheema recommends flushing home water systems after long absences, using distilled water in humidifiers and medical devices, and avoiding exposure to mist in public areas. These precautions can help prevent the spread of Legionella bacteria and protect vulnerable populations.