By Joseph BENSON

Across Ghana’s river basins, the damage of illegal small-scale mining, or galamsey, is visible from space. The once-clear Pra, Ankobra, and Birim Rivers now flow brown with silt and mercury, choking ecosystems and raising the cost of potable water.

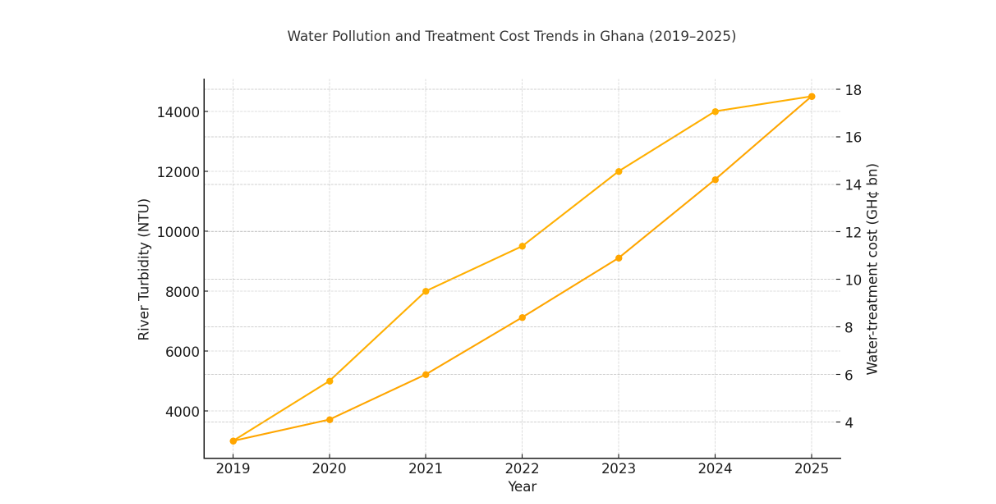

The Ghana Water Company reports turbidity levels of 12,000–14,000 NTU, seven times its plant design limit of 2,000 NTU, and warns that treatment costs could quadruple by 2030 if pollution continues.

Meanwhile, satellite data show that Ghana lost nearly 35,000 hectares of forest cover in 2024, with almost a third attributed to illegal mining along waterways. These are no longer environmental statistics; they represent a national economic liability measured in lost productivity, rising energy bills, and weakened public trust.

Yet technology now offers a way to reclaim both rivers and confidence. Artificial intelligence, combined with drone and satellite systems, is reshaping how Ghana monitors, predicts, and responds to illegal mining. What began as a policing tool has become a platform for innovation, enterprise, and governance renewal.

The Scale of the Challenge

Ghana’s Minerals Commission estimates that over 1 million people engage directly or indirectly in artisanal and small-scale mining, with about 30 percent operating illegally. While ASM accounts for nearly 40 percent of gold output, it also drives an estimated GH¢17.7 billion in environmental and water-treatment liabilities each year.

The World Bank calculates that degraded watersheds could reduce Ghana’s agricultural productivity by 6 percent by 2030, while the Ghana Statistical Service attributes 5–7 percent of annual GDP losses in affected districts to land degradation and pollution.

Graph 1: Environmental and Economic Cost of Galamsey, 2019–2025” showing rising treatment costs and GDP impact.

Traditional enforcement methods; manual patrols, checkpoints, and sporadic raids, are expensive and often reactive. In many cases, by the time inspectors arrive, excavators have been moved and pits refilled. The need for a predictive, continuous, and evidence-based system is now undeniable.

The Rise of AI and Remote Sensing in Environmental Governance

Drones and satellites have given regulators eyes in the sky, but it is artificial intelligence that gives those eyes meaning. Through machine-learning models trained on thousands of aerial images, AI can automatically detect changes in terrain color, water turbidity, and pit geometry. Algorithms classify imagery into “legal,” “suspended,” or “illegal” mining zones, and send alerts when anomalies occur.

Globally, such systems are transforming environmental oversight. Indonesia uses AI-powered drones to monitor coal-mine tailings; Peru integrates satellite imagery with predictive models to identify mercury contamination hotspots. Ghana’s advantage is its manageable geography and growing digital infrastructure, which allow near-real-time data flows between drones, the Minerals Commission, and district assemblies.

This integration of AI and remote sensing marks a fundamental shift—from reactive enforcement to predictive governance. Instead of waiting for environmental damage to be reported, authorities can now anticipate and intervene before rivers turn brown or forest cover vanishes. The value lies not only in detection but in the pattern recognition that AI enables seasonal fluctuations in sediment load, correlations between rainfall and illegal pit expansion, and even the migration of artisanal miners from one district to another.

By linking these insights to licensing data, Ghana can build a dynamic compliance map—an evolving picture of risk that guides inspections, resource allocation, and community engagement.

Over time, such a system can also reduce human discretion and potential bias in enforcement, ensuring that regulatory actions are guided by data rather than influence. The goal is not surveillance for its own sake but stewardship—harnessing technology to protect livelihoods, restore trust, and balance economic ambition with ecological responsibility.

Ghana’s Emerging Technological Response

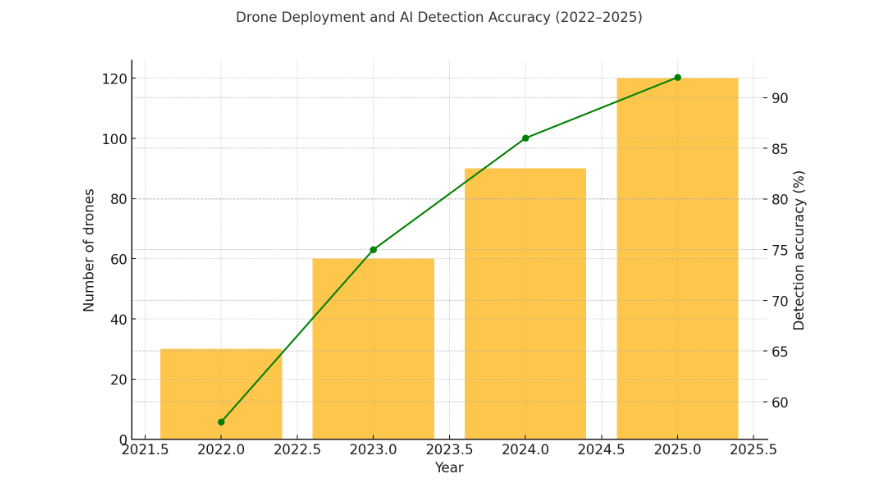

Since 2023, the Minerals Commission and the Ghana Armed Forces have deployed over 120 drones across major mining corridors. These drones conduct 1,500 flight hours monthly, capturing imagery that feeds into a new National Mine Surveillance Centre in Accra. The Ghana Space Science and Technology Institute contributes satellite data from the Sentinel and Landsat programs, while universities provide annotation support to train AI models.

Early results are promising. In pilot districts such as Tarkwa-Nsuaem and Wassa East, automated image recognition has improved illegal-site detection accuracy from 58 percent in 2022 to 92 percent in 2025, cutting average response time from five days to less than twelve hours. The Minerals Commission estimates that the system has helped prevent roughly ₵400 million in potential gold-smuggling losses since its introduction.

Graph 2: Improvement in Detection Accuracy and Response Time, 2022–2025.

These technologies do not eliminate human oversight; they augment it. Field teams still validate AI alerts, but with clearer priorities and evidence trails that strengthen prosecution and deterrence.

Turning Technology into Local Enterprise

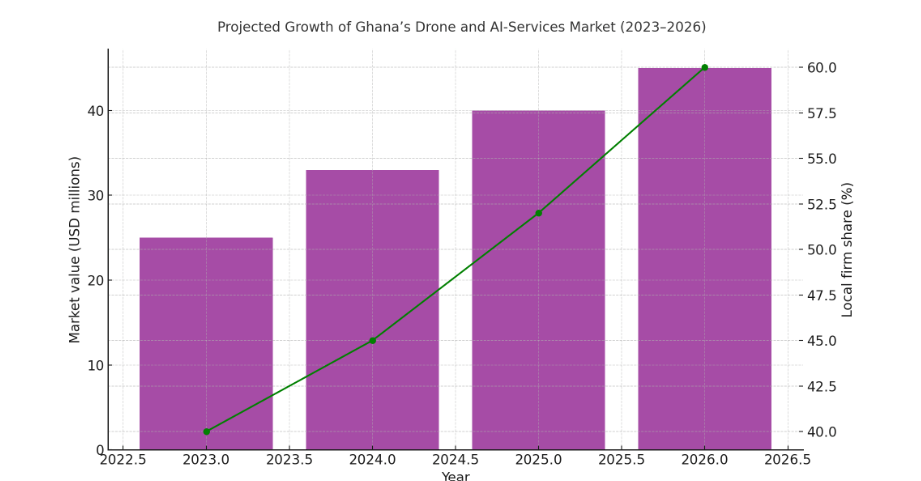

Beyond enforcement, the integration of AI and drones opens an entirely new commercial frontier. Local firms are already emerging to manage drone fleets, process imagery, and develop predictive analytics for government and private mining clients.

Start-ups such as AquaGeo Analytics and DronOps Africa are piloting cloud platforms that convert aerial data into actionable environmental metrics. Others provide contract services to regional assemblies, offering vegetation mapping, pit reclamation tracking, and compliance dashboards. This aligns with Ghana’s broader industrial policy: turning regulation into opportunity and governance into enterprise.

By 2026, Ghana’s drone-services market is projected to exceed US $45 million annually, with an estimated 60 percent of revenue coming from mining and environmental monitoring. Local universities and hubs—including the Kumasi Hive and Academic City College—now run certification courses in geospatial data science and drone operations, building a skills pipeline that links youth employment directly to ecological recovery.

Graph 3: Projected Growth of Ghana’s Drone and AI-Services Market, 2023–2026.

Safeguards and Governance: Ethics, Data, and Accountability

Technology succeeds only when embedded within trust. Ghana’s draft Digital Governance Framework provides for judicial authorization of high-resolution surveillance and requires encrypted data storage for all environmental imagery. The Commission also plans to publish quarterly transparency reports showing number of drone flights, detected violations, and enforcement outcomes.

Civil-society organizations advocate additional safeguards: community notification when drones operate overhead; independent audits of AI-based decisions; and sunset clauses for data retention. These measures are essential to avoid the perception of technological overreach. The goal is not surveillance for its own sake but stewardship grounded in law, transparency, and human rights.

Lessons from Other Developing Economies

Ghana’s approach sits within a wider global trend. Brazil’s Amazon Protection System (SIPAM) integrates AI and satellites to reduce deforestation alerts by 30 percent in two years; India’s Jharkhand State uses drone mapping to formalize artisanal mines, doubling tax compliance within twelve months. The common denominator is the shift from punitive enforcement to data-driven inclusion, turning informal operators into traceable, tax-paying enterprises.

For Ghana, success will depend on maintaining this balance: using AI to detect and deter illegal mining while simultaneously creating legal, technology-enabled pathways for small operators. Formalization remains the sustainable antidote to galamsey.

Building Partnerships for the Future

The next phase requires deeper collaboration. The private sector can supply capital and The next phase requires deeper collaboration. The private sector can supply capital and innovation; universities can refine algorithms; and regional bodies such as the African Union’s Digital Transformation Strategy (2024–2030) can provide frameworks for interoperability. Development partners, including the World Bank’s Digital Ghana Project, are already allocating funds for geospatial infrastructure and data governance.

These partnerships are particularly important because no single institution can manage the technical, environmental, and regulatory dimensions of AI-enabled monitoring alone. Mining companies possess vast operational data that can enrich AI models; universities and research centres can translate that data into predictive insights; and government agencies can set the standards that ensure technology is deployed responsibly.

Together, they can create a unified platform where satellite imagery, drone footage, water-quality readings, and licensing databases speak to each other in real time, reducing duplication and accelerating enforcement.

Public-private partnerships could expand coverage to all riverine districts by 2027, supported by drone hubs, maintenance facilities, and training academies. Each step not only protects ecosystems but generates skilled employment, positioning Ghana as West Africa’s centre for mining-tech expertise. As these systems mature, the country can begin exporting its models and expertise to neighbours confronting similar challenges, turning a difficult national problem into an engine of regional leadership and economic opportunity.

Conclusion: Technology That Restores Trust

Artificial intelligence and drones are not substitutes for governance; they are instruments that can make governance visible. When properly regulated, they offer a chance to reclaim degraded land, restore rivers, and rebuild public confidence in state capacity.

Ghana’s experiment is more than a fight against illegal mining; it is a model for how a developing nation can fuse innovation with integrity. Each flight hour and each algorithm trained adds a layer of transparency to a sector once defined by opacity. If the momentum continues, anchored in ethics, community participation, and entrepreneurial inclusion, AI will not only hover over rivers; it will help heal them.

The author is an entrepreneur, a business development consultant, and philanthropist based in the USA but globally connected with world renowned companies. Passionate about education and a founder of diverse businesses globally.

Provided by zaianews. (zaianews.com).